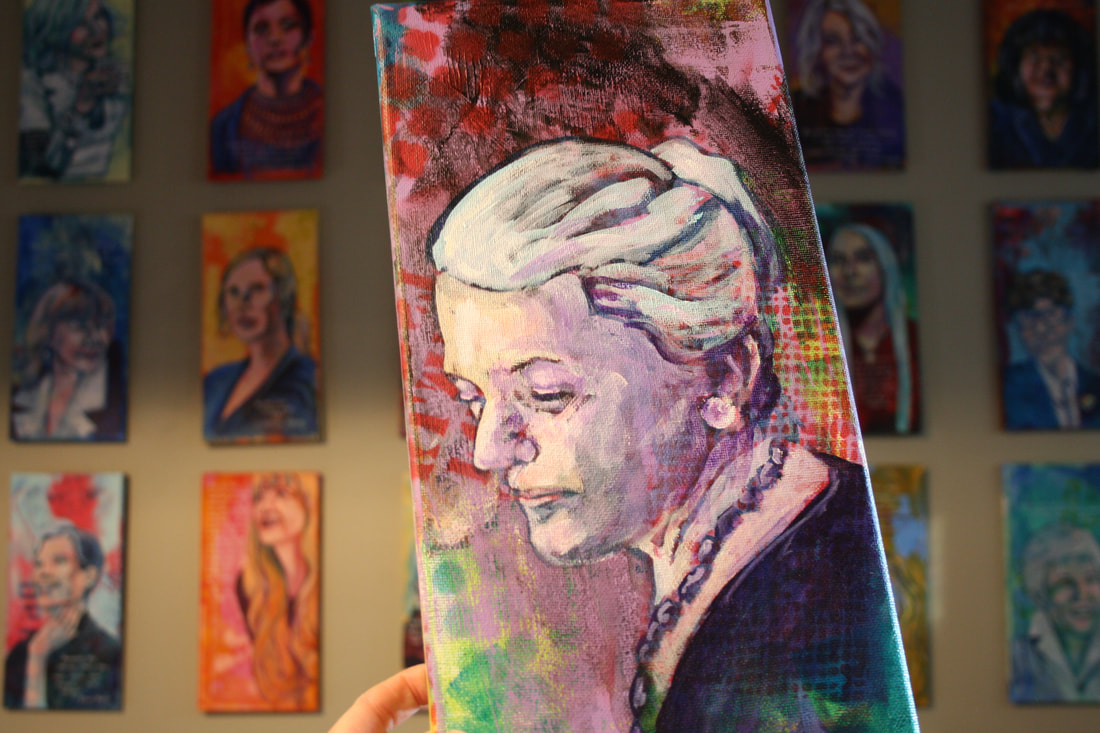

What I wanted more than anything was to be able to look after myself and make sure that every other woman in the world could do the same. Magazine editor and women’s movement champion. Doris Anderson was a long-time editor of Chatelaine magazine and a newspaper columnist. Through the 1960s, Doris Anderson pushed for the creation of the Royal Commission on the Status of Women, which paved the way for huge advances in women’s equality. She was responsible for women getting equality rights included in the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. She authored a number of books, including three novels and an autobiography — Rebel Daughter — and sat as the president of the National Action Committee on the Status of Women. Anderson became an officer of the Order of Canada in 1974 and was promoted to Companion in 2002. She was also a recipient of a Persons Case Award and several honorary degrees. Photo: Barbara Woodley; courtesy of Library and Archives Canada/1993-234 NPC.

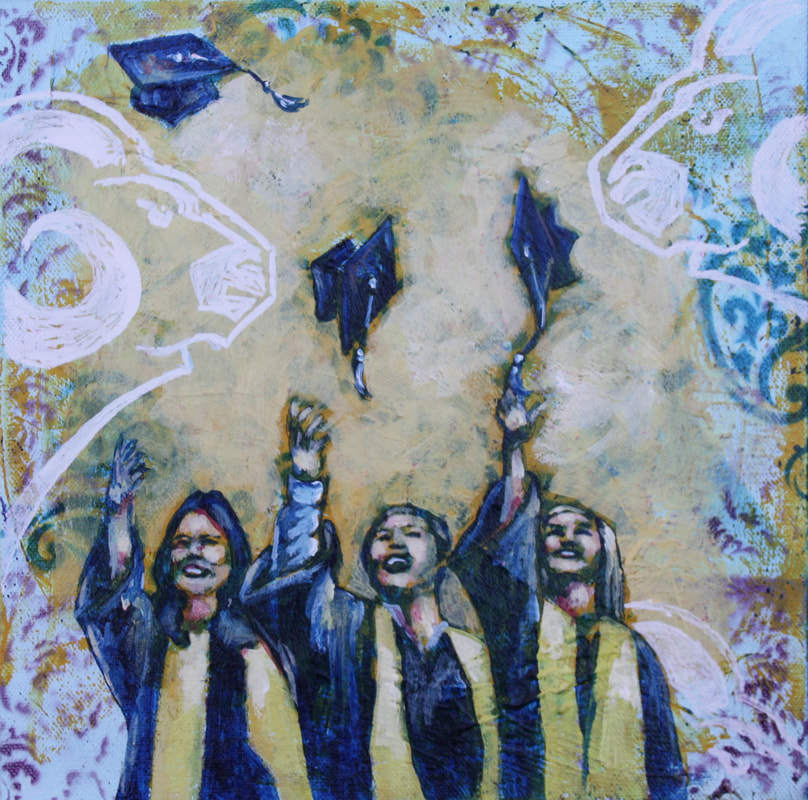

~ Canada's Great Women Doris Anderson headed Chatelaine from 1957 to 1977, opening its pages to everyone from the “prairie housewife to the Toronto sophisticate,” said former colleague Michele Landsberg. Under her watch, the magazine expanded its readership to one in every three Canadian women. It led the conversation on issues from divorce to birth control to abortion. Yet as editor, she earned less than half what her male predecessor made. ~ Christopher Reynolds, Toronto Star The Amazing Airdrie Women Awards hosted annually by AirdrieLIFE magazine celebrated Bert Church High School with the workplace award. I have loved creating these paintings as awards and am so grateful for the magazine and their dedication to local arts and artists. I wanted to capture the celebratory nature of education and educators when milestones are reached and to incorporate their colours (blue & gold) and logo in the design. High school can be a difficult time, but those teachers who encourage and support their students make all the difference and, in fact, it was my high school art teacher, Mrs. Roth, who encouraged and supported me in my creative endeavours. Without her and the support of the school, I would not have pursued this life, which has been absolutely incredible. Sadly she is no longer with us, but I thought of her while I painted and wished I could celebrate my successes with her today.

I've been enjoying painting the birds that flit around our garden for the past few weeks...there is something so soothing about watching these little creatures. For his birthday this summer, I gave my husband a bird bath, bird book and an embroidered bird by artist Lesley Bergen (it's amazing!) so I've really been enjoying learning more about all the little birds that live in our trees. I feel very lucky as I get to sit cozily in my reading nook to watch them in our evergreens out the front bay window.Anyway, these three are headed to Lineham House Galleries in Okotoks (Left: Barn Swallow, 20"x10"; Top: Cedar Waxwing, 12"x12" Bottom: Blue Jay, 12"x12"). I'm really pleased with how they turned out.

When the last tree is cut, the last fish is caught, and the last river is polluted; when to breathe the air is sickening, you will realize, too late, that wealth is not in bank accounts and that you can’t eat money. A member of the Abenaki Nation, Obomsawin, whose last name means “pathfinder,” returned with her family to the Odanak reserve near Sorel, Quebec, when she was six months old. Her father was a guide and a medicine maker, and her mother ran a boarding house. Her time on the reserve was idyllic; she delivered her aunt’s homemade bread and sang with abandon in her aunt’s rocking chair.

She moved with her family from the reserve to Trois-Rivières when she was nine years old. Though the transition was difficult, her father’s death from tuberculosis when she was 12 pushed Obomsawin to rebel against the bullying and the promotion of European cultural superiority in school. Leaving Trois-Rivières at age 22, she spent time learning English in Florida before settling in Montreal in the late 1950s. Following her debut as a singer at a concert at New York City’s Town Hall in 1960, Alanis Obomsawin made appearances on reserves, in schools and prisons, at music festivals and on television. In 1966, she was profiled on the CBC program Telescope for her activism and “near superhuman” efforts to fund — through donations, concerts and lectures — a swimming pool for the Odanak reserve after the local river was deemed too polluted. She has performed throughout North America and Europe, self-accompanied on a hand-drum or rattle. Her repertoire includes traditional Aboriginal songs, as well as stories in English and French. Her 1984 album, Bush Lady, is perhaps the best example of her musical style. Accompanied by the hand-drum, and occasionally flute, oboe, violin and cello, Obomsawin sings and tells stories in several languages. In “Mother of Many Children,” a track of intermixed chanting and French spoken word, she begins in English: “From earth, from water, our people grew to love each other in this manner. For in all our languages, there is no he, or she. We are the children of the earth, and of the sea.” Though primarily known for her filmmaking, Obomsawin has not abandoned her performance roots. She has appeared at the Guelph Spring Festival, the National Arts Centre in Ottawa, the Place des Arts in Montreal, the Mariposa Folk Festival (where she was coordinator of Aboriginal peoples' programming from 1970 to 1976) and at WOMAD (Harbourfront, 1990). She also appeared regularly for several years in the 1970s on the Canadian version of the children's program Sesame Street. Obomsawin gave her first concert in 30 years when she sang Bush Lady in its entirety at Le Guess Who? Festival in Utrecht, Netherlands, in November 2017. She received a standing ovation from the crowd of 800 people, and later told the Montreal Gazette, “When they all stood up, I thought I was going to pass out. I was so touched. I just couldn’t imagine that they would like it so much.” Bush Lady was re-released on vinyl, CD and digital formats by Montreal-based Constellation Records in June 2018 to mark the album’s 30th anniversary. Obomsawin also performed the album at Montreal’s Monument-National on 28 September 2018 as part of the POP Montreal music festival. She received many other requests to perform but has done so selectively. “It’s not an easy thing for me,” she told the Gazette in September 2018. “What I sing about is not easy. I feel every word. I’m always worried I might cry.” After noticing her in the CBC Telescope feature in 1966, Wolf Koenig and Bob Verrall, producers at the National Film Board (NFB), hired Obomsawin as a consultant on projects that related to First Nations peoples. In 1971, she directed her first film, Christmas at Moose Factory, and in 1977 she became a permanent staff member at the NFB. Committed to redressing the invisibility of Indigenous peoples, Alanis Obomsawin’s filmmaking style resides in the unique ability to pair Indigenous oral traditions with methods of documentary cinema. Amisk and Mother of Many Children, produced and directed in 1977, combine interviews with music, dance, drawings and archival images to validate the history of Indigenous peoples across Canada. Of her films on young people, Richard Cardinal: Cry from a Diary of a Métis Child (1986) is the best-known, and perhaps the most striking. A dramatic account of a young boy’s suicide, it led to a government report on social services for Indigenous foster children in Alberta, though little has been done to alleviate such problems (see also Suicide Among Indigenous Peoples in Canada). Obomsawin’s films have documented the work of Indigenous organizations to help young people overcome alcohol and drug abuse (Poundmaker's Lodge: A Healing Place, 1987), and provide services to homeless Indigenous peoples in Montreal (No Address, 1988.) Her films on the struggles of the Mi'kmaq over fishing rights (Incident at Restigouche, 1984) and the Mohawk-government standoff at Oka in 1990 (Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance, 1993) have been widely acclaimed, and have brought Obomsawin national and international recognition. - Winston Wuttunee, Zuzana M. Pick, Paul Williams, The Canadian Encyclopedia “Hope” is the thing with feathers

That perches in the soul And sings the tune without the words And never stops - at all And sweetest - in the Gale - is heard And sore must be the storm That could abash the little Bird That kept so many warm I’ve heard it in the chillest land And on the strangest Sea Yet - never - in Extremity, It asked a crumb - of me. ~ Emily Bronte I began this little collection of minis (4x4) by painting our little Boler trailer (we love it!) which led to painting all of the vintage items around us. The little cabin was from a photograph I had taken of one of the oldest homesteads near Beaver Mines Lake last summer; the antique lantern sits on our bookcase; the kettle has been well-used on camping trips throughout the years; and the Coleman stove was inherited from an old bachelor uncle whom we thought the world of. The idea for this little series began when we stayed in a 1920s cabin at Johnston Canyon in the Rocky Mountains while the pastel backgrounds were inspired by Wes Anderson movies and their vintage themes. It was just so fun to create something very different for me, but still inspired by the things I love and that draw my attention. These pieces symbolize the perfect little 'Get-Away'.

When you develop communities, it’s like working in the trenches. You train the people to become self-sufficient. Thelma Chalifoux was born mid-winter of 1929, in Calgary. The first year of her life was marked by both flood and famine; in June the Bow and Elbow Rivers burst their banks immersing the community in a deluge of water, dams and bridges were washed away by the heaviest rains the area had seen in decades. Later that year, the nation’s financial institutions failed to keep their stocks afloat, thereby causing the economy to plummet. In these unsteady times, Thelma’s parents were a bedrock force, setting the groundwork for Thelma’s greatness. As a child of the Depression, Thelma’s first decade was one of both scarcity and abundance, as the world around her tightened its proverbial purse strings, she was shown the value of cooperation and community, sacrifice and solidarity. Upon this foundation, a truly incredible woman was built; a Métis matriarch who has brightened the world and served all people by standing up for children, women, the elderly, families and the larger Métis nation. Just as a house has walls, windows and floors to hold it steady and upright through time, no matter the weather, no matter the forces that may press against its pillars, Thelma’s parents built within her an adaptability and graciousness that continues to this day.

Thelma’s family was considered small for that era, she had two sisters and two brothers. Her fondest childhood memories are of farm life, cattle drives and horses, and warm summer days spent with her family at the Calgary Stampede. Despite the droughts, and the distances her father had to travel for work, no matter the shortage of new shoes or clothes, Thelma most remembers her parents’ resilience and resourcefulness, their connection to the Indigenous community and their absolute respect for their Métis culture. One of Thelma’s favorite mantras comes from her father, “We are the Métis and we are the best!”. Those early years built within her a solid set of values and real clarity of purpose; Thelma’s sense of self, her love for family, her respect for culture and her fierce work ethic united to create one of the Métis People’s most notable citizens. Having lived 86 years, Thelma has seen a lot of changes for women, for families and for the larger Métis community. In the 1950’s, an era in which neither women’s nor Indigenous rights were given much space in the national mindset, Thelma left an unhealthy relationship to create a new life for herself and her children. In many ways, not to minimize Thelma’s later accomplishments, this act could be viewed as her most brave and is certainly testament to her greatness as a matriarch. Motherhood has many roles and responsibilities, it is never-ending, selfless and fraught with a myriad of energy depleting duties. Her faith in God and her personal strength are what kept Thelma going during those years of single parenthood, but it was her connection to the Métis community that allowed her to thrive. Friendship has always meant a lot to Thelma as she has never liked doing things alone, her sensibility is that people are best served by many hands and minds. Her circle of lifelong friendships with other steadfast women have produced a myriad of organizations that continue to serve the Métis and First Nations community. By the grace of God and the goodness of others, including her older children who kept an eye on the little ones while she worked, Thelma was able to keep food on the table and a roof over their heads. Because she knows, firsthand, the struggles people experience, Thelma has always worked for the betterment of others. She is a mother, a friend and an advocate for the voiceless. Amongst her many accomplishments, Thelma is a founding member of The Slave Lake Native Friendship Centre and the Michif Cultural Institute in St. Albert. She was the the first Métis woman to receive the National Aboriginal Achievement Award and the first Métis and first Aboriginal woman to be appointed to the Senate of Canada. The world can be a daunting and cruel place, a place of coldness and apathy. When life gets to be too much, people need somewhere to rest, someone to lean upon. Thelma Chalifoux is so much more than a person, she is a woman of tremendous tenacity and boundless compassion, a venerable sacred place where others may find solace. If asked to describe her greatest accomplishment, it is doubtful that Thelma would list off her lengthy resume, but rather, she is more likely to say that her success lives in her children and grandchildren, her broad circle of friends and allies, and, in her deep connection to the Métis community. This is the house that Thelma built for us, this is the home where our hearts may find sanctuary. A house of strength and compassion, a home filled with light, faith and laughter and hope. ~ Jenna Chalifoux ✨Exciting news!

I am happy to offer MENTORING for Emerging Artists through @LevellingUp, a global artist community launched by Canadian artist @julie.deboer.art. By artists, for artists! 🚩 Join me! Learn more @levellingup. Our mentorship group STARTS SOON! Together you, me, and a small group of up to just 7 other artists will meet online for 2 hours every month. Between sessions you'll work on homework alongside your group members. We’ll tackle the hurdles and struggles you face as an Emerging Artist, like how to: 🔺 Create & sustain a THRIVING business as an artist, one you can actually live off of 🔺 Build your BRAND & MARKET yourself 🔺 Go SOLO online or approach GALLERIES for representation 🔺 Manage your time for max PRODUCTION 🔺 And how best to achieve YOUR goals I’d love to see YOU there! 👉 Join the community at levellingup.ca. First we only want to be seen, but once we’re seen, that’s not enough anymore. After that, we want to be remembered. “There’s a part of me that feels like the life of Station Eleven was something like being struck by lightning or winning the lottery,” says author Emily St. John Mandel, reflecting on the success of the novel that served as the focus for this year’s NEA Big Read.

Adam Byko: You got your start in dance before moving into writing. Did you feel you transitioned skills or a mentality from one artform to the other, or were they two totally different things in your mind? Emily St. John Mandel: I mean, mostly they’re totally different things. But I think dance is really good for developing this kind of fire and self-discipline, which I don’t think is applicable just to the arts. I think if you’re a dancer first, you might go on to become a more disciplined attorney or anything else you do in your life. But it definitely helps with writing. So much of writing is just forcing yourself to sit at your desk and write a novel. So, you know, discipline’s important. In that sense, one’s probably related to the other. AB: Speaking of discipline, I am so curious about your process for writing. Both the books I’ve read of yours have really interesting structures. With Station Eleven there’s a graphic novel, theater, paparazzi, and on top of that a whole post-apocalyptic wasteland. How does this all make the leap from your head to the page? Do you start with one plot and then things spiral, or are you juggling multiple plots right from the get-go? ESJM: I start with one thing usually. With all of my books, it’s just been one thing. Sometimes it’s just kinda a wisp of a premise… For Station Eleven, my original idea was partly just to write something really different from my previous three books. I felt like I was drifting in the direction of crime fiction. And that’s kind of a delicate point because I really like crime fiction — I have such respect for what crime writers do. But you can get trapped in these marketing categories and it’s hard to ever break out as a writer. So I wanted to do something a bit different. And my starting point with Station Eleven… I guess it was that Shakespeare performance [of King Lear] that opens the book. Even before I knew the book was going to be post-apocalyptic, it was always going to start with that actor dying of a heart attack. AB: So in the original conception of the book, there was no mass epidemic? ESJM: Yeah, it was going to be set completely in the present day. I was going to write this — in retrospect — somewhat precious book about the importance of art in our lives. Which it still is, but it was going to be just about the lives of actors in a travelling company. The trials and tribulations of this underfunded Shakespearean troupe. And it wasn’t until I started writing that that I added the post-apocalyptic element. It seems like a bit of a leap, but I wanted to write about our technology, and I thought an interesting way to do that would be to contemplate its absence. AB: A major theme of the book is summed up in the quote “Survival is Insufficient” [from Star Trek], especially in regards to the arts. Your book came out in 2014, and the world has continued to change since then. As someone making art in this world, does that phrase mean more to you now or has it had a continuous influence? ESJM: I would say it’s been continuous. There are definitely things about the world in 2019 that trouble me deeply, that weren’t even on the horizon in 2014. Like consensual reality? That’s something I really miss. [Laughs]. When we all used to have one set of facts from which we drew different conclusions. That was a nice thing that I took for granted in retrospect. So you can make an argument that the world’s become more bleak, but I feel like we always think we’re living at the end of the world. You know, when have we ever felt like it wasn’t going to be catastrophic? So there’s some comfort in that. AB: I want to go back to the structure question and how you braided so many narratives together. I’m so curious about the order. When did each element manifest in the draft as you were editing the novel? ESJM: Right, so I know the first element was Arthur dying on stage. I always knew it was going to be a nonlinear narrative because that’s the only way I know how to write novels if I’m being honest here. I knew I could kill him off on page three and we could still get a lot about his life. I think my next element was actually Miranda. I wasn’t sure for a long time how that character fit into the narrative though I remember all kinds of weird variations. Like at one point she was the executive assistant of Arthur’s sister Claire, who doesn’t exist by draft number three. I just always had a vision of who she was as a character: Graduated art school, practicing her art around the margins of her day job, which, as the graduate of a program in contemporary dance, was something I knew a lot about. So it was Arthur, then it was Miranda, and then I think the next element was the post-apocalyptic stuff, when I started writing about the Travelling Symphony. Clark was the last element, and kinda the last character who came together. With Clark — and this goes back to what happens to your work when you don’t have an outline — he was originally such a minor character. I was originally thinking, “Well Arthur’s throwing a dinner party. He should really have an old friend.” And I found I just really liked him. He was fascinating to me. He was the only character who I had a really vivid picture of. During my time at The Rockefeller University, there was a postdoc who I used to see all over campus. I don’t know his name or what lab he worked in. But he had the most fabulous sense of style. He was probably, I don’t know, early thirties. Probably six foot three, very thin, wore these great vintage suits, which, because he was so tall, ended about four inches above the ankle, with bright pink or striped socks and his hair was shaved off on one side and floppy on the other and sometimes pink? I think it’s fair to say that scientists are not particularly renowned for their sense of style — writers aren’t either [laughs] — but this guy just had an incredible look about him. And for some reason I was picturing him as I was writing the young Clark, and he just took over and became more and more interesting to me. That was the last major element of the story to come together. I was really playing around endlessly with the structure of this book. I remember I was changing the order of entire sections, pretty much right up to the end. AB: Let’s say we had a Museum of Civilization, and you could put five books in there. What five books would you want to save for those post-apocalyptic future generations? ESJM: That’s a great question, I don’t think I’ve ever had it framed in quite those terms. I think the first one I would pick would be Suite Francaise by Irene Nemirovsky. It’s an incredible novel, and the story behind it is equally amazing. Nemirovsky was from Russia originally and emigrated to France as a teenager in the 20s. By the time the Second World War broke out she had converted to Catholicism from Judaism, but that didn’t save her. She was arrested and sent to Auschwitz because she was Jewish. She died there. She left behind two young daughters who survived the war. And she also left behind a notebook filled with minuscule handwriting. The daughters assumed that that was her diary, and it was too painful to even contemplate reading it. They never opened this thing until decades had gone by and they were well into adulthood. They had this moment where they have to come to terms with this and read their mom’s diary. They got out a magnifying glass and started transcribing. It wasn’t a diary. It was a magnificent novel about the Nazi invasion of Paris. So I think there’s a lot in there. I choose it both because it’s beautiful, but also I suppose it touches on that larger theme of how you maintain or fail to maintain your humanity in a moment where Nazis are invading Paris so to speak, in a moment where things are precarious and everything’s falling apart. So that’s the first book I’d choose…. I don’t know about the other four [laughs]. I’ll have to think about that. ~ Adam Byko, Arts & Culture, UFCToday |

|