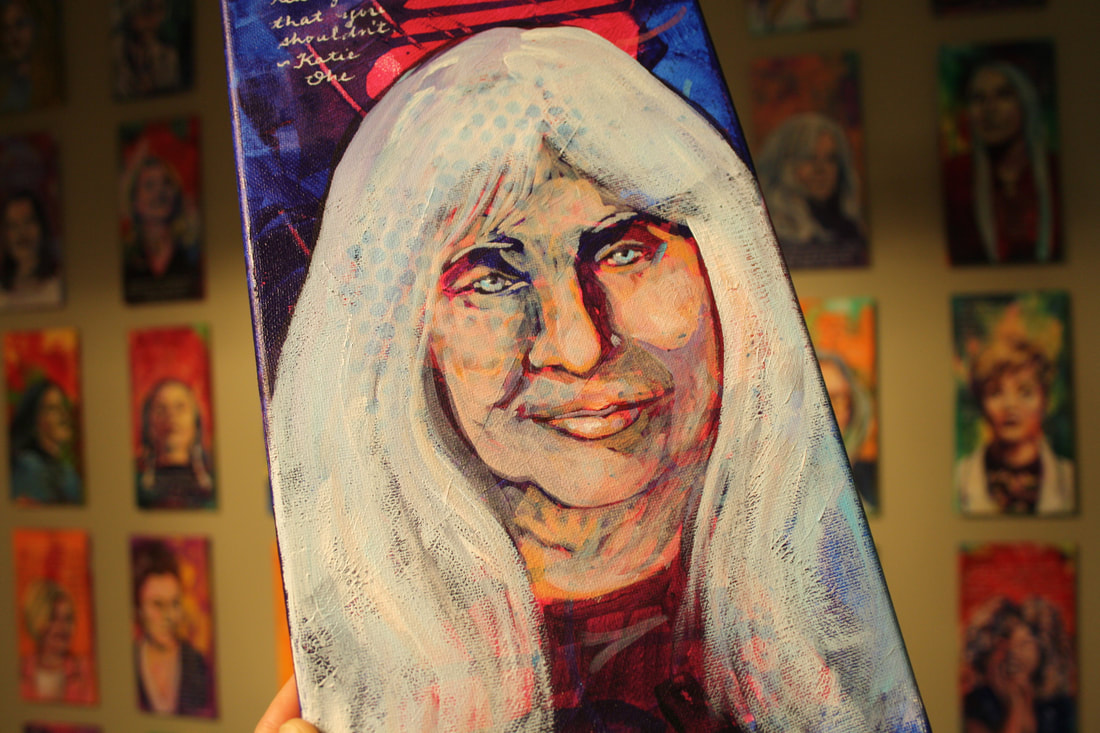

I want my sculptures to induce or to invoke touch before you really think that you shouldn't. Active in the Calgary arts community since the mid-1950s, when she began her formal arts education at the Provincial Institute of Technology and Art, (now the Alberta University of the Arts,) Ohe subsequently pursued training in Montreal, New York City, and Verona. In the early 1960s, a time when a tradition of European landscape painting still had a stronghold on the artistic production in the province, and very few artists were making sculpture at all, Ohe became one of the first artists in Alberta to make abstract sculpture. She began to utilize a variety of new materials, skills, and techniques, including the use of pre-fabricated objects and industrial processes. Through her work and her teaching practice, (she taught at the Alberta College of Art and Design from the early 1960s until her retirement in 2016,) Ohe became a major influence on the sculptural practice in the region.

Embracing elements of reductive geometry, repetition, and visual harmony, Ohe has developed a body of work that is at once connected to Minimalism through its purity and unity of form, but is also affective, idiosyncratic, sensual, and concerned with personal experience, memory, and the perception of the natural world. She is perhaps best known for her masterful kinetic sculptures. Beginning in the early 1970s, after much thought and experimentation with ways to rise above familiar heavy and static sculptural forms to achieve a sense of weightlessness, dynamism, fluidity, and optical confusion, Ohe perceived that changes in sculptural configuration through movement coupled with a viewer’s physical and physiological interaction would be essential in realizing these goals. To that end, much of her work since that point is distinguished by its radically tactile nature. The quality of surface became inextricably important to the success of her sculptures; works such as Horizontal Loops (1973), Zipper (1975), Upper Flow (1975-76), and Venetian Puddle (1977-78) were chromed and polished to a perfect, seductive smoothness, which would, as Ohe often remarks, “induce or provoke touch before you think that you really shouldn’t.” Movement introduces an integral element to the space within and surrounding the sculptures, which in turn influences the perception of their form. Combinations of undulating, spiralling, fluidly shimmering and reflective shapes generate a sense of visual instability and optical uncertainty—and also a sense of humour and playfulness—which makes the viewer and their experience an essential part of the work. The 1980s introduced other external influences to her oeuvre and generated new ways of thinking and making. The ambitiously scaled installation, Skyblock (1981-82), a configuration of suspended horizontal bars branching into a spiral herringbone pattern, was originally designed as a proposal for a public commission in the Gulf Canada Building. The work was conceived as a way to bring the viewer within an immersive environment of reflective material and into a physical relationship with the idea of an infinitely changing linear pattern. Although Ohe didn’t receive the public commission, she proceeded to fabricate the work on a smaller scale. In 1983, Ohe travelled to Japan and there drew insight from traditional rock gardens and their elemental sense of contemplation. Kinetic works from the mid-1980s to early 1990s, such as Drummer Boys (1988) and works from the Guardian series deployed new, more earthy materials such as cast and tinted aluminum and aggregate stone, which introduced a shift toward a warmer, textured surface and a more diffuse and softer reflection of light. These works are both more elemental and more figurative, and movement is principled on the contemplatively rhythmic swing of ringed pendulums. Ohe’s floor-based series of works such as Typhoon (1984), Monsoon (2006, 2011), and Chuckles (2015) utilize powder coating and colour to induce intuitive touch. The collective movement of these groupings emphasizes the importance of the space around the sculptures, their relationship to each other, and to the viewer. When the sculptures are collectively in motion, their unique movements and spatial relationships generate a situation wherein the mind and eye cannot immediately comprehend the logic of form and space. Although they appear simple and minimal, each of Ohe’s works is extremely labour intensive and technically precise. Their creation often involves years of experimentation, trial and error, engineering, and fabrication to create the correct effect and affect through movement. Her sculptures have agency; they are active, vital, and compel you to touch them. Ohe’s work reminds us that seeing is not the only form of perceiving our environment; that the relationship among the visual, physical, poetic, and psychological compose a way of knowing the world rooted in comprehensive and intellectual challenge and disruption. ~ Esker Foundation Comments are closed.

|

|